Sanura

When Bram Stoker penned *Dracula* in 1897, he could hardly have envisioned the enduring influence his creature of the night would exert on literature, cinema, and popular culture. More than a century later, Count Dracula remains one of the most identifiable figures of gothic horror. The character has transcended its origins as a literary vampire in a late Victorian novel and become a cultural icon of fear, mystery, and fascination with the supernatural. To understand why Dracula has had such a persistent influence, it is useful to examine its historical context, themes, symbolism, and lasting cultural relevance.

Dracula came into being during the late nineteenth century, when the Western world was grappling to adapt to rapid social, scientific, and cultural change. The Industrial Revolution had transformed how humans lived and worked, Darwin’s theories of evolution had disrupted traditional religious beliefs, and new ideas about psychology, sexuality, and human nature were beginning to take shape. Gothic fiction, popular since the late eighteenth century, provided a way for writers to dramatize anxieties about such changes in stories of horror, the supernatural, and the unknown. Stoker, a London-based Irish writer, tapped into this tradition but gave it a new lease of life by creating a villain whose menace combined old superstition with modern anxieties. Count Dracula is not just a vampire but a symbol of invasion, corruption, and moral decay in a time when British society was obsessed with order and progress.

The novel itself is structured in a non-traditional way. It is an epistolary novel, meaning the story unfolds through letters, diaries, newspapers, and telegrams. This structure gives the novel a realistic feel, as if the reader is piecing together the facts from actual documents. It also mirrors the Victorian period’s focus on evidence, observation, and documentation, especially in the scientific and legal professions. At the same time, the fragmented narrative adds to the novel’s mood of uncertainty, since each character has knowledge of the truth only up to a point. The epistolary format works to bring into relief the struggle between rational modernity and the supernatural horror of Dracula.

Dracula himself is one of literature’s most memorable villains. A tall, thin, pale man with pointed teeth and hypnotic eyes, he is terrifying, yet charismatic and seductive, able to manipulate those around him through fear and fascination. This duality makes for a subtle villain. On one hand, he is prime evil, feeding on the blood of the living and bringing a plague of death. On the other hand, he is forbidden lust, especially in the way he attacks female protagonists. Victorian audiences would have picked up on the sexual implications of scenes in which Dracula sucks blood from the necks of women. The vampire’s violent but sensual bite symbolized fears of sexuality, gender roles, and moral corruption at a time when strict social codes governed personal behavior.

One of the strongest aspects of the novel is its treatment of women. Women like Lucy Westenra and Mina Harker are at the center of the novel, and their experiences highlight the tension between traditional female roles and the danger of female independence. Lucy, portrayed as pure and innocent, is victimized by Dracula and suffers a horrid transformation into a sexually aggressive vampire. Her death and destruction represent society’s requirement to punish and control female transgression. Mina, on the other hand, is intelligent, resourceful, and loyal and plays an important role in the chase of Dracula. And even she has to be protected from corruption, and her innocence serves as a rallying point for the male heroes. In these portrayals, Stoker is reflecting Victorian anxieties about female roles in a world that was transforming.

The book is also preoccupied with science and superstition. Dracula has his origins in Transylvania, a remote country in Eastern Europe that Victorian readers associated with ancient folklore and inexplicable dangers. He represents a pre-modern, almost medieval threat bursting into modern Britain. The protagonists combat him using both scientific methods and old legend. Professor Van Helsing, for instance, is a doctor who respects modern science but also believes in folk medicine such as garlic, crucifixes, and stakes of wood. This mixture of superstition and science captures the tension of the era, when rational progress coexisted uncomfortably with lingering belief in the supernatural. The novel suggests that evil can be defeated only by faith and knowledge, by reason along with tradition.

Another layer of significance in Dracula is in the way it handles foreignness and invasion. More than just a vampire, the Count is also a foreigner from Eastern Europe who threatens the stability of England, the heart of the British Empire. His quest to spread his influence in London reflects fears regarding immigration, contagion, and cultural pollution. At a time when the empire was at its peak, Stoker’s novel conveyed the fear that Britain itself might be vulnerable to invasion or decadence. The image of Dracula crossing borders and bringing with him a dark contagion resonated with a culture anxious about its place in a changing world order.

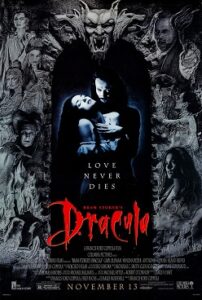

Despite its roots in nineteenth-century anxieties, Dracula has enjoyed an unusual afterlife. The novel was not an immediate bestseller when it was first published, but it quickly became considered one of the classic works of gothic literature. In the twentieth century, it generated hundreds of adaptations for theatre, film, and television. The 1931 film *Dracula*, starring Bela Lugosi, established many of the visual conventions now common in vampires: the cape, the accent, the aristocratic bearing. Later interpretations, such as Christopher Lee’s menacing performances in Hammer Horror films or Gary Oldman’s tragic portrayal in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film, have kept reinventing the character for new generations. Each adaptation reflects the phobias of its time, whether they be of sexuality, illness, politics, or technology.

Dracula has influenced many other vampire stories as well. From Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire* to Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series, modern vampire literature owes a profound debt to the template Stoker created. Even when vampires are romanticized as misunderstood outsiders in some of these works, the ghost of Dracula is never far behind, reminding audiences of the vampire’s original form as a figure of horror. Even in contemporary culture, with vampires making appearances in comic books, television dramas, and computer games, Count Dracula remains the benchmark against which all the others are measured.

Dracula’s enduring popularity is that it can portray universal fears in such a manner that these can be transposed into different cultural situations. The vampire can stand for disease, foreign invasion, illicit desire, or even the disintegration of social order. Because these fears are never entirely allayed, Dracula inhabits the imagination to this day. While the character’s charisma and immortality make him perversely alluring, blurring fear and desire. Audiences and readers are repelled and drawn, captivated by a tale that will not diminish in its power to unsettle.

In conclusion, Bram Stoker’s *Dracula* is far more than a gothic vampire novel. It is a cultural document that represents the anxieties of late Victorian Britain and yet is flexible enough to speak to future generations. In its treatment of such issues as sexuality, science, superstition, invasion, and the role of woman, the novel resonates with deep human fears that still reverberate today. Dracula himself, in his fusion of horror and attraction, continues to inspire new interpretations in literature, film, and popular culture. More than a century after his creation, the Count still lives on in the imagination, proof of the timelessness of the way that horror stories can also reveal society’s deepest desires and fears.